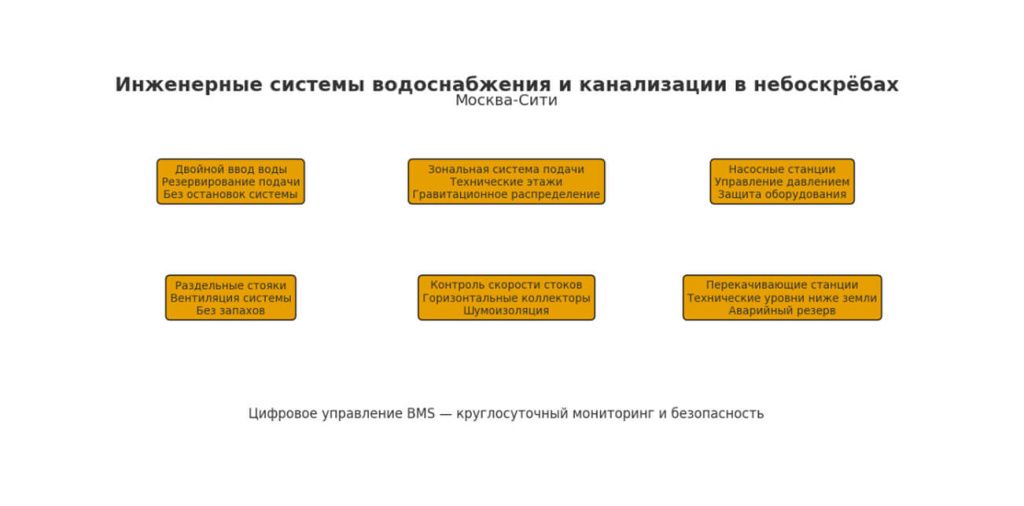

The design of water supply and sewerage systems in Moscow City's high-rise buildings is based on current regulations (SNiP 2.04.01-85*, relevant SP for high-rise buildings and internal systems), as well as actual hydraulics and fire and environmental safety requirements. Below is how this works in practice, with figures, standard solutions, and terminology.

Where does the water come from and how does it get into the tower?

Imagine: tens of thousands of people live and work in the skyscrapers of Moscow City every day. Life is in full swing here—restaurants and offices are open, air conditioners are on, hot water runs in apartments, and post-workout showers are available in fitness clubs. For all this to be possible, water must be pumped tens and even hundreds of meters into the air without interruption and in the right volume.

But where does such a huge amount of fresh water come from? How is it delivered to buildings with 50, 70, or 100 floors? And what is needed to ensure that the water pressure at the highest levels is as comfortable as on the ground floor?

The answer lies in a special, high-tech urban water supply system that connects Moscow City with the region's reservoirs and rivers, and then distributes water to towers via powerful underground pipelines and intelligent engineering nodes.

Water source

Moscow-City is fed by the city system: a mixture of surface water (Moscow River / Volga), which has undergone multi-stage purification (mechanical, coagulation/flocculation, filters, ozonation/activated carbon).

Water transportation

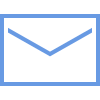

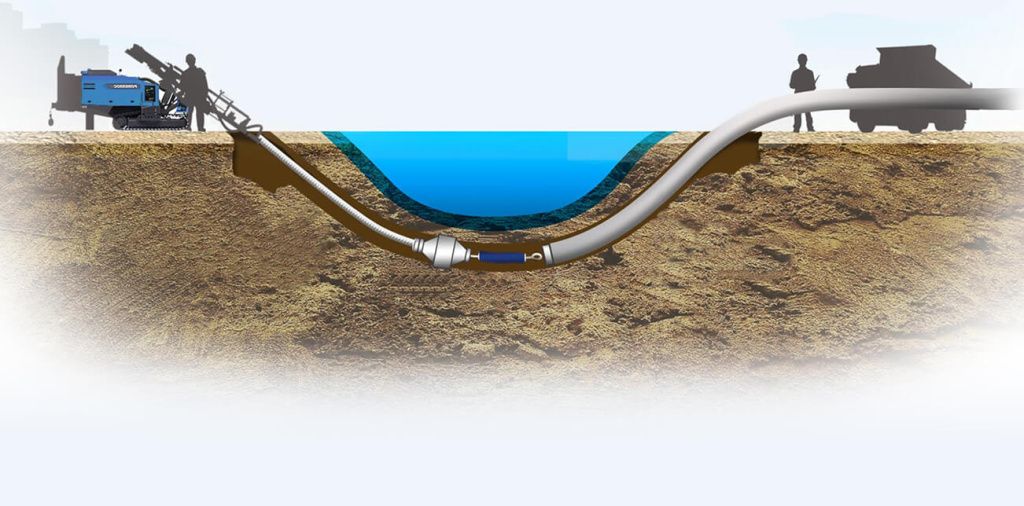

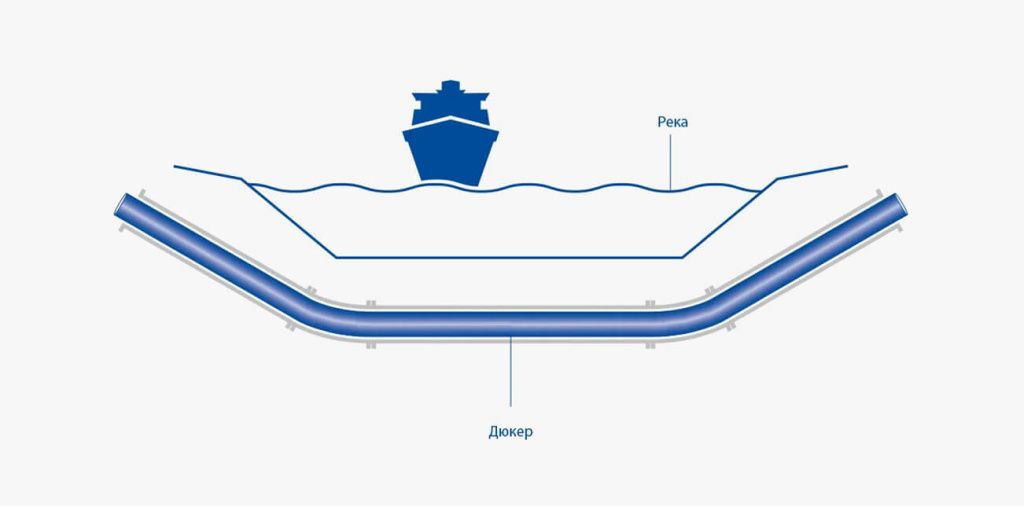

Siphons (pressure pipelines under the riverbed) have been installed for the district. In 2020, an additional 2D400 pressure inlet was installed to accommodate the growing number of consumers.

Daily water volumes

For a separate tower - thousands of m³/day, and the actual consumption is significantly reduced due to recirculation (DHW), pressure regulation and energy management.

Building entry point

-

Two independent inputs (N+1 reliability): if one fails, the power line automatically switches to the other.

-

In the underground part (-1/-2 floor): metering and preparation unit - mesh/disc filters, metering devices, shut-off and check valves, bypass.

-

Operating pressures at the inlet: usually 0.4–0.6 MPa (4–6 bar), vary depending on the region and time of day.

Term: N+1 - redundancy of one unit in excess of the required minimum.

Term: A siphon is a pressure pipeline laid below the bottom of a watercourse.

Term: Bypass - an alternate path for water around equipment.

Why is zonal (cascade) supply necessary?

Trying to supply water to the very top of a skyscraper with a single "regular" water supply system would immediately create several problems. The higher the floor, the greater the pressure required. This means the pipes and plumbing fixtures below must withstand enormous loads. This is expensive, dangerous, and completely inefficient: the pipes below might not hold up, and the water above will barely flow.

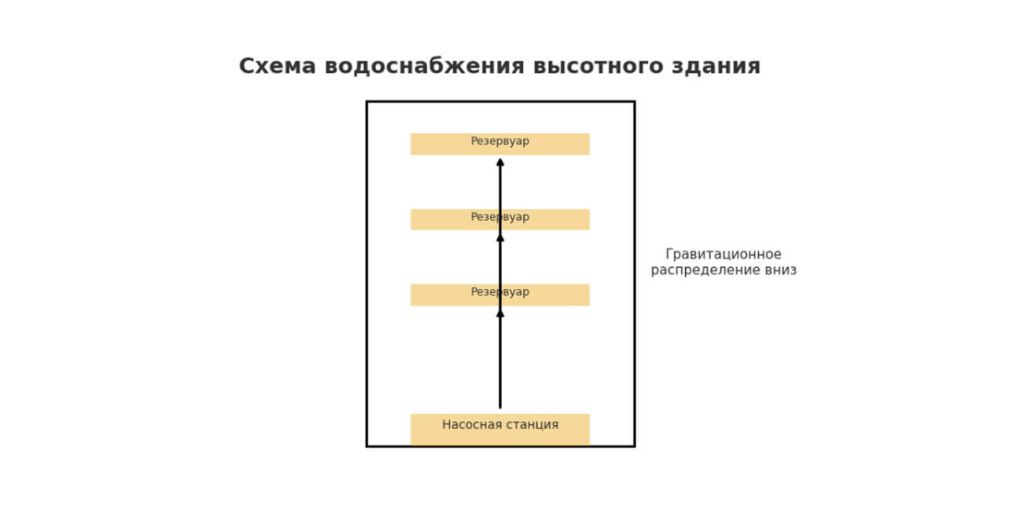

So engineers came up with an elegant solution: dividing the high-rise building into separate zones. Each zone is like a miniature house within the skyscraper. Water is pumped up to the required height, then flows into a reservoir, and then flows down under its own weight, without wasting any energy.

This way, the tower receives water gradually, floor by floor, and the pressure at each level remains safe and comfortable. This also increases reliability: if an accident occurs in one zone, the others continue to operate.

The static pressure of water increases with height: 1 m of water column is ≈ 0.098 bar. At 80 m, the pressure difference is already ~7.8 bar. If water is supplied "bottom-up" in a single circuit, the lower sections become overpressured, increasing the risk of water hammer, expensive thick-walled fittings, and accidents.

Zoning principle

The building is divided into vertical zones of 30–45 meters (approximately 10–15 floors). Each zone:

-

has its own pumping group and storage tank on the technical floor;

-

It operates at its own pressure, and then the water is distributed downwards by gravity.

Typical zonal ladder (example):

Basement → technical floor ~22nd (≈80–90 m) → technical floor ~32nd → ~43rd → ~54th → … to the top.

Up the riser there is a pump, on the technical floor there is a tank, down the zone there is gravity.

Plus: we eliminate static pressure, reduce energy costs, and increase fault tolerance.

Pumping stations, reservoirs, regulation

To ensure that water not only reaches the upper floors but also does so reliably, skyscrapers employ armies of pumps and reservoirs. Their job is to maintain the required pressure so that water flows from a faucet on the 70th floor with the same force as on the 5th.

How does it work?

-

In the underground levels and on the technical floors there are powerful pumps that lift the water upward.

-

At intermediate heights, reservoirs are installed where the water “rests” and then flows down on its own – under the influence of gravity.

-

To ensure that the pressure is comfortable and does not "tear" the plumbing, pressure reducers are installed, and special compensators smooth out the differences.

-

If one pump fails, the backup one will immediately switch on.

-

Even if the power goes out, the system will continue to operate thanks to autonomous generators.

Pumps

-

Type: Multistage centrifugal pumps with variable frequency drives (VFD) to maintain a set pressure in the system.

-

Composition: main + reserve (N+1) + jockey pump (low flow to “maintain” pressure without starting the main one).

-

Performance: from tens to hundreds of l/s per group depending on the zone and combined modes (cold water supply, hot water supply, fire extinguishing).

-

Power supply: two input lines + diesel generator for emergency situations.

Storage tanks

-

Purpose: buffer, elimination of peaks, jet break and transition to gravity distribution.

-

Volume: from several m³ to tens of m³ per zone (depending on the estimated flow rate and required autonomy).

-

Equipment: level gauges (float/piezo), overflow, flushing, bactericidal treatment, leak sensors.

Maintaining pressure

-

The zones maintain a working pressure of 3.5–5.5 bar.

-

At the entrances to apartments/offices there are pressure reducers (PRV) with settings of 2.0–3.0 bar.

-

The lines contain hydraulic accumulators/compensators to suppress water hammer.

Terms:

-

VFD — variable frequency drive;

-

PRV — pressure reducer;

-

Water hammer is a short-term pressure surge caused by a sharp change in flow velocity.

Cold/hot water supply, circulation and sanitary safety

Hot and cold water in skyscrapers also requires high-level engineering. In a typical home, hot water quickly cools in the pipes, requiring a wait for it to reach the tap. High-rise buildings don't have this luxury: waiting 2–3 minutes means enormous water and energy losses.

Therefore, the system is designed so that water is always at the right temperature:

-

cold - remains cold even on the upper floors,

-

hot - constantly circulates so as not to cool down,

-

The temperature is controlled automatically to prevent the growth of dangerous bacteria.

This is monitored by heat exchangers, pumps, and automation—everything is hidden on the technical floors and operates without interruption.

-

DHW – cold tap water (usually 5–15 °C depending on the season).

-

Hot water is produced in heat exchangers on the technical floors; the supply line temperature in the riser is 60–65 °C, the return line temperature is 55–60 °C (anti-legionella).

-

DHW circulation is essential to prevent stagnant areas; balancing is required on each leg.

-

At hygienically critical facilities, thermal disinfection/antibacterial modes are carried out according to a schedule.

Term: Anti-Legionella - prevention of bacterial growth in hot water.

Fire water supply and automatic fire alarm system

A high-rise building is like a small city, and its safety depends on how quickly a fire can be stopped if it does break out. In ordinary buildings, the primary reliance is on firefighters outside. But in a skyscraper, especially one 200–300 meters tall, outside help may simply not arrive in time.

Therefore, the Moscow City towers have their own fire extinguishing systems, fully integrated with the water supply:

-

on each floor there are fire cabinets with hoses,

-

Automatic sprinklers are hidden in the ceiling and open automatically when the temperature gets high,

-

Water for extinguishing is stored in special tanks and supplied by separate pumps.

If a fire alarm is triggered anywhere, the system is immediately activated, and firefighting begins before emergency services arrive. This ensures that people have time to safely evacuate the building and that damage is minimized.

In high-rise buildings, water supply is integrated with fire systems:

-

Internal fire-fighting water supply (IFWS): fire hydrants in cabinets on floors, single stream flow rate of 2.5–5.0 l/s (as specified), supply time is designed with a reserve.

-

AUPT (automatic fire extinguishing):

Sprinklers - with temperature-sensitive lock (typical settings 68–72 °C).

Drenchers are open sprinklers for water curtains.

-

Water reserve for fire (usually a separate volume in the lower part + boosters on technical floors).

-

PT pumps are separate, with automatic switching on and reserve according to the N+1 scheme.

Internal pipelines: materials, speeds, diameters

The pipelines inside skyscrapers are a complex network, comparable in scale to the utilities of a small city. Water flows through dozens of kilometers of main lines and hundreds of branches, so the materials and parameters of the pipes are subject to the highest standards.

The main pipelines that carry water up and down the technical floors are made of galvanized or stainless steel—these pipes can withstand high pressures and temperature fluctuations. Closer to the consumers, in offices and apartments, modern polymer and composite pipes are used: they are lighter, quieter, and better protected from corrosion.

Water velocity plays a crucial role. To ensure stable pressure and long-lasting pipes, cold and hot water mains maintain flow rates of approximately 0.7–1.5 m/s. Indoors, the flow rate is lower—around 0.5–1.0 m/s—to prevent noise and water hammer.

Pipe diameters gradually decrease as the building ascends. At the entrances to a skyscraper, they can be DN200–DN300—large steel mains. In the upper areas, DN50–DN100 diameters are used, and indoors, smaller DN15–DN25 diameters are used, leading directly to the plumbing fixtures. This ensures the system operates efficiently and safely at any height.

In the large Moscow City towers, the total length of such pipes reaches hundreds of kilometers—and all of this is hidden within the walls and technical rooms, operating around the clock and unnoticed by those inside.

-

Materials: galvanized/stainless steel on main lines; polymers/composites on "thin" wiring; mandatory anti-corrosion coatings and sound insulation.

-

Speeds (recommendations):

Cold/hot water supply main: 0.7–1.5 m/s;

Intra-apartment wiring: 0.5–1.0 m/s.

-

Diameters: decrease towards the upper zones (approximately DN200–DN300 at the inputs → DN50–DN100 at the top, then DN15–DN25 for intra-apartment installations).

-

In a large tower, the total length of utility pipes can reach hundreds of kilometers.

Sewerage: wet/dry riser, calming areas, storm drain

In skyscrapers, sewer systems are also zoned to prevent wastewater from accelerating to dangerous speeds and creating noise and negative pressure in the pipes. Two vertical risers are used for drainage: the "wet" one carries household wastewater, while the "dry" one provides ventilation and protects the traps from air infiltration. Every 10 to 25 floors, the flow is deliberately "calmed"—at technical levels, the wastewater flows into horizontal collectors, where its velocity slows.

Horizontally, the sewer system flows by gravity with slight slopes, and the connections to the appliances are angled to reduce turbulence. Rainwater from the roof and condensate from air conditioners are collected separately—in large buildings, this volume can amount to tens of cubic meters per day. At lower levels, where gravity flow is no longer possible, pumping stations operate, pushing wastewater into the city network.

Vertical risers

-

Wet riser (DN100–DN150) – domestic and sewage.

-

Dry riser (DN100) - ventilation, connected with crosses, prevents vacuum, maintains water seals of devices.

The speeds in the riser without dampers easily exceed 4–7 m/s, so the building is divided into cascades (10–25 floors), and horizontal collectors/expanders are installed on the technical floors to reduce the flow energy and noise.

Horizontal sections

-

Gravity slopes: DN50 → 0.02; DN100 → 0.01 (1–2%).

-

The fittings are installed at 45–90°, aeration is provided by a dry riser and local aerators (one-way valve to compensate for the vacuum in the sewer).

Rainwater and condensation

-

Roof drains, facade channels → storm risers DN100–DN200 → underground collectors with catcher grates.

-

Condensate from VRF/VRV (variable refrigerant flow) and fan coil units (indoor air conditioning units) is a separate network; during peak hot days, the volume can reach tens of cubic meters per day for a large building.

Pumping

-

In underground levels and parking lots (below the discharge level) there are fecal/drainage pumping stations with grinder baskets, float/ultrasonic control and redundancy.

Terms:

A water seal is a water plug in a siphon that blocks out odors.

Cascade is a group of floors between technical floors with a calming flow.

BMS: dispatching and predictive operation

A modern skyscraper is a smart building. All water supply and sewerage systems are integrated into a single BMS (Building Management System) control platform. It monitors pressure, water flow, pump operation, hot water temperature, and even leaks in the most hidden places in real time. If a deviation occurs, the system reacts instantly: automatically switches zones, shuts off the damaged sections, and alerts the dispatcher.

At the same time, operations are carried out according to strict regulations. Sewage systems are regularly flushed with high pressure, pipes are inspected using video diagnostics, meters are calibrated, valves are serviced and replaced, and hot water is periodically heated to high temperatures to prevent the growth of dangerous bacteria. All this allows the Moscow City towers to operate continuously, safely and comfortably for the thousands of people inside.

BMS (Building Management System) combines:

-

pressure, level and flow control points;

-

pump statuses (VFD, alarms, bearing temperature);

-

leaks (cable tapes/spot sensors in pits);

-

water quality events (t°, residual oxidation potential, bactericidal modes);

-

scenarios: automatic zone switching, branch shutdown in case of a breakthrough, “night” pump frequency curves.

Service — according to regulations: hydrodynamic cleaning of sewerage systems, endoscopy of risers, verification of meters, inspection of valves, balancing of circulation, anti-legionella treatment (thermal shock, chemical regime).

Scheduled maintenance includes:

-

High-pressure sewer cleaning to prevent blockages and unpleasant odors.

-

Checking internal pipes with a camera to detect wear or damage in advance (endoscopy of risers).

-

Verification of water meters to ensure they accurately calculate consumption.

-

Checking and servicing shut-off valves - taps, valves, reducers.

-

Setting up hot water systems

which returns the water back to the heating system so that it does not cool down in the pipes (balancing the circulation).

-

Prevention of bacteria

(anti-legionella) - periodic heating of water to a high temperature or special treatment to prevent the development of dangerous microorganisms in the system.

Resource conservation and sustainability

-

Frequency control reduces pump energy consumption by 20–35% in variable modes.

-

DHW recirculation and heat recovery reduce water/heat consumption.

-

Smart setpoints (night/holiday profiles) reduce leaks and peaks.

-

Low-roughness materials and proper hydraulics mean lower pressure losses → lower pump frequencies.

Terms and abbreviations (glossary)

-

DHW/CWS – cold/hot water supply.

-

PRV — pressure reducer.

-

VFD — variable frequency drive.

-

IFP — internal fire-fighting water supply.

-

AUPT — automatic fire extinguishing system (sprinkler/drencher).

-

BMS — building management system.

-

A duct is a supply pipeline under the river bed.

-

DN — nominal pipe diameter (mm).

Conclusion

The water supply and sewerage systems of Moscow City skyscrapers feature multi-zone hydraulics, smart automation, and fire preparedness. Cascade systems, variable-frequency drives, properly sized diameters, and sewer dampers ensure the safe operation of buildings 200–370+ meters tall without overloads, odors, or accidents. Trends for the coming years include even more accurate BMS analytics, reduced specific water and energy consumption, and standardized components to speed up installation and maintenance.

Living in skyscrapers requires engineering on a different scale: here, water becomes not just a utility, but a high-tech service operating around the clock, pushing the limits of technical capabilities.

Moscow-City is one example of how a systems approach, digital management, and multi-contour architecture can elevate quality of life and safety to the level of modern megacities.

Advertising on the portal

Advertising on the portal